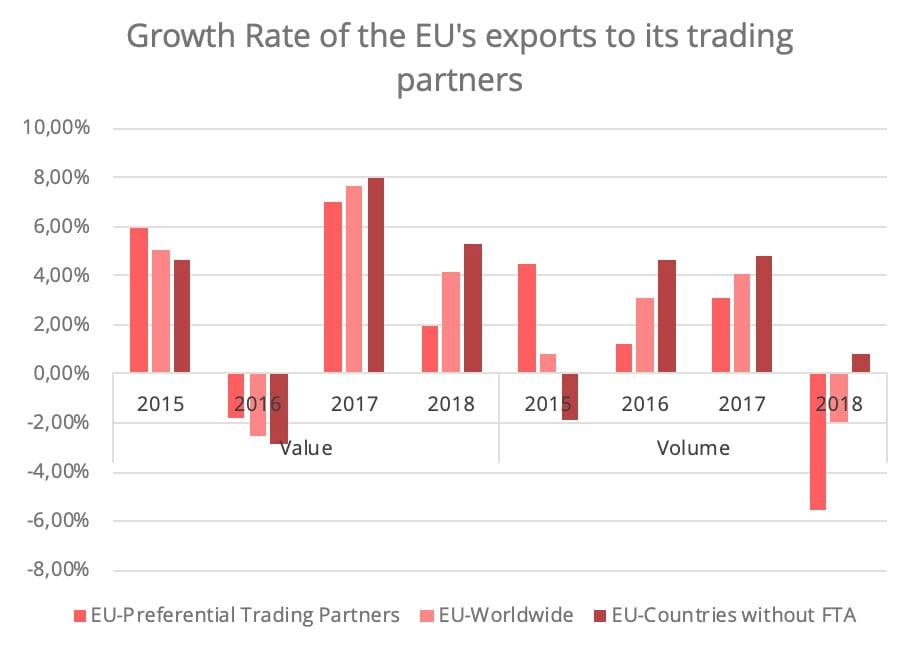

According to the 3rd annual report on the implementation of trade agreements published by the EU on October 14th, in 2018, EU exports to preferential trade partners grew by 2%, whereas the total growth of the EU's exports worldwide was 4%. The figures for imports are similar: 4.6% in comparison to 6.6%. These are rather disappointing figures, but more opportunities could emerge in the future.

While Free Trade Agreements (FTA) were expected to boost trade between the EU and its preferential partners, the trade data from 2018 shows a rather disappointing result. Export and import shipping volume between EU and its preferential partners, have both decreased by 6% and 1.3%, respectively, compared with the 2% decrease and 2.3% increase in EU's exports and imports with all non-EU states. 31% of the EU’s trade (33% of exports and 29% of imports) was made with countries benefiting from preferential Free Trade Agreements in 2018.

In this article, we will try to unravel this reduction of the EU's export volume to its preferential partners in 2018 and briefly look at the EU’s exports to its preferential trading partners in 2019.

Figure 1 - Data source: Eurostat

Four categories of trade agreements

Overall, the EU categorizes its preferential trading partners into four groups based on the emphasis placed on a different area of trade: First-Generation, Second-Generation, Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas (DCFTA), and Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA).

- First-Generation refers to trading partners having concluded FTAs with the EU before 2006, with a focus on tariff elimination.

- Second-Generation emphasizes on developing liberalized and regulative trade relations. It extends to new areas (intellectual property rights, services and sustainable development, …)

- DCFTA agreements focus on the enhancement of trade relationships with the EU's neighboring countries.

- EPA agreements are asymmetrical between the EU and countries from African, Caribbean, and Pacific regions, with an emphasis on global development to the south. Partners liberalize 80% of their market over 15 to 20 years, and the EU fully opens its market from day one.

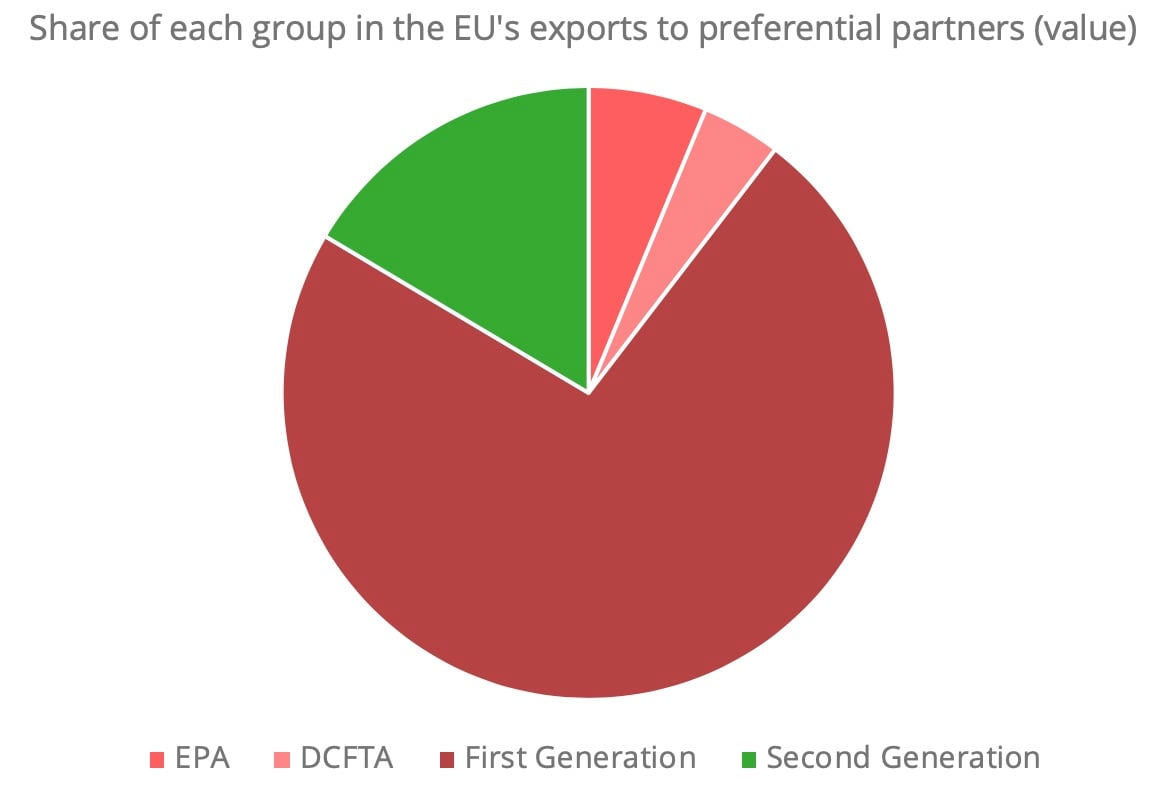

A substantial contribution from historical partners

Among the four groups, in both value and volume, trade with partners from the first-generation is the highest, accounting for over 70% of the total trade between the EU and its preferential partners. This is followed by the second-generation, EPA, and DCFTA (figure 2). The top three preferential trading partners, Switzerland, Turkey, and Norway, all belong to the first-generation group.

Figure 2 - Data source: Eurostat

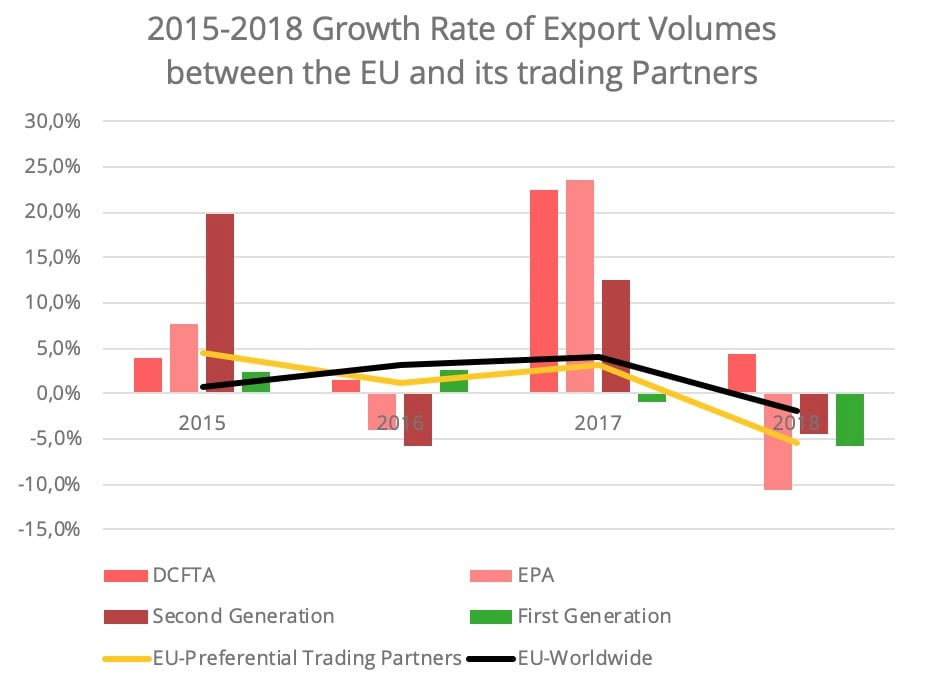

The impact of the global economic slowdown

In 2018, the EU's export volume to all groups decreased, with the exception of the DCFTA zone (figure 3). The decrease in the first-generation group accounts for most of the loss in export shipping volume. Specifically, the decrease in the EU’s exports to Turkey and Switzerland accounts for nearly half of the EU's total loss of export shipping volume with its preferential trading partners. The drop in EU exports to Turkey alone accounts for more than 66% of the overall decline in shipping value and 39% in shipping volume. This is due to a significant decrease in imports of mineral fuels and steel from the EU in 2018.

Figure 3 - Data source: Eurostat

The slowing down of the global economy resulted in a reduced demand for European goods in 2018. The growth rate of the worldwide export volume from the EU also dropped from 4% to -2%. Notably, the underperformance of the Turkish economy in 2018 resulted in a decreased demand for imports from the EU in almost every sector (based on the division of HS codes). In 2018, Turkey's worldwide imports had decreased by 4.6% and its imports from the EU dropped 8% in value, and 16% in volume.

Moreover, the lack of modernization of the FTAs between the EU and some first-generation trading partners, may also negatively affect the development of trade between the two parties. Some terms may no longer be suited to ongoing trading relations and some current issues are not covered in the original agreements. The EU is holding negotiations with Mexico and Chile aimed at modernizing the FTAs. In 2016, the EU proposed to modernize their agreement with Turkey, however preparation for this has yet to get off the ground.

2019: A fruitful year

As we are approaching the end of 2019, it is time to see how the EU’s exports to its preferential partners are faring so far. Can we see a better result in comparison to 2018?

2019 has been a very fruitful year for the EU in terms of finalizing preferential agreements, with the conclusion of two FTAs, with Vietnam and Mercosur, and one with Japan entering into force and yet another with Singapore about to enter into force on November 21st. As such, 41% of the EU's trade will soon be covered by preferential agreements. The EU-Vietnam and EU-Mercosur agreements still need to go through the ratification process, particularly as the Mercosur agreement has raised growing concerns from the European food industry and environmental groups. The implementation of the EU-Japan FTA in February, as we have discussed before, has shown to have produced positive results, as more European wine and cheese are now finding their way onto Japanese dining tables.

Overall, the latest data available shows that as of August 2019, the EU’s export value to preferential trading partners enjoyed a 2.8% growth compared with the same period last year. However, the export volume decreased by 2.7%, compared with the first eight months of 2018. This decline is mainly due to the reduction in EU exports to Turkey and South Korea. The producers of mineral fuels and the automobile manufacturers are the ones that are particularly feeling the pinch in these two markets. A sharp drop in German car exports to South Korea and Turkey in the first eight months of 2019 has been observed.

We may observe a gradual improvement of the EU's economic situation, along with that of Turkey as it recovers from 2018’s currency crisis. However, this recovery seems to be fragile, due to various domestic economic challenges and geopolitical tensions, as suggested by a European Commission forecast. This situation creates further uncertainties as to the trade between the EU and Turkey. This uncertainty is also present in the trade relations with South Korea. The EU’s exports to South Korea may continue to struggle as its economy is still slowing down.

Do Free Trade Agreements really benefit European trade?

To return to the question that was raised at the beginning -does the EU benefit from FTA agreements-, this is a question that cannot be merely answered by a simple yes or no. In 2018, the EU also enjoyed a bigger market share in certain countries. There is continuous growth in its trade with DCFTA countries, particularly EU exports to Ukraine, which was up 9% in value and 4.5% in volume in 2018. Similarly, the EU’s exports to Canada increased by 4% in volume and 10% in value in 2018, which was the first year of the EU-Canada FTA implementation. The increase came particularly from the growing demand in the Canadian market for European fruit and chemical products.

These two sectors are also areas in which the EU experienced global market growth with all their preferential trade partners. According to reports, in 2018 the agricultural sector and chemical sector have enjoyed growth rates of 2.2%, and 2.5% respectively in export value to markets in preferential trade partner countries.

The food sector is certainly one that has generally benefited from the FTAs. While EU cheese and wines may experience some hard times ahead in the US market due to the latest US tariffs, the FTA agreements have helped to expand the market into other states and regions, such as Asia. Outside of the Japanese market, the EU-Singapore FTA which will soon be entering into force (November 21st) the result of which will be the lifting of all tariffs on European food entering into the Singaporean market.

Furthermore, export growth rate is only one of the effects of FTA implementation. They aim to establish regulative trade relations, by addressing intellectual property protection, sustainability, and labor rights, for example. This will help to establish healthier and more sustainable trade relations that will improve the EU’s long-term competitiveness in the global market.