The Covid-19 pandemic gives a fresh impetus to an idea which has already been floated around the table by the global supply chain’s stakeholders: relocation from China. The economic arguments are now joined by political considerations.

The pandemic has meant that relocation from China has come to the forefront once again. Firstly, because companies are seeking to diversify their supply chain and thus enhance resilience. But also because governments of countries such as Japan, France and the US are supporting this move by providing funds to assist their firms in seeking alternative options outside of China. Simultaneously, governments of potential relocation sites, such as Vietnam, Thailand or India, are acting to attract companies to relocate to their countries.

“China plus One” Strategy

China's deep integration in the global value chain means that a complete withdrawal of manufacturing is almost impossible. The prominent market and skilled labor are substantial advantages to operating in China, as shown in a survey conducted by the EU Chamber of Commerce in China. For many European companies, their manufacturing activities are “in China, for China”. The percentage of respondents planning to move out of China is 11%, down from 15% in 2019, whereas 12% plan to diversify their supply chain by seeking alternative suppliers outside of China. While Covid-19 did affect business decision-making, it was not considered as a major reason to relocate, with only 4% considering moving out of China due to the pandemic.

In the current climate, the most likely scenario being envisaged for the post-pandemic period would be something the media has labelled “China plus One”, meaning diversifying suppliers with additional manufacturing sites outside of China.

Who could be the "plus Ones"?

According to the EU Chamber of commerce survey, among the respondents considering relocating from China, half of them cite either Europe (27%) or Southeast Asia (23%) as potential locations.

1. Central Eastern European Countries

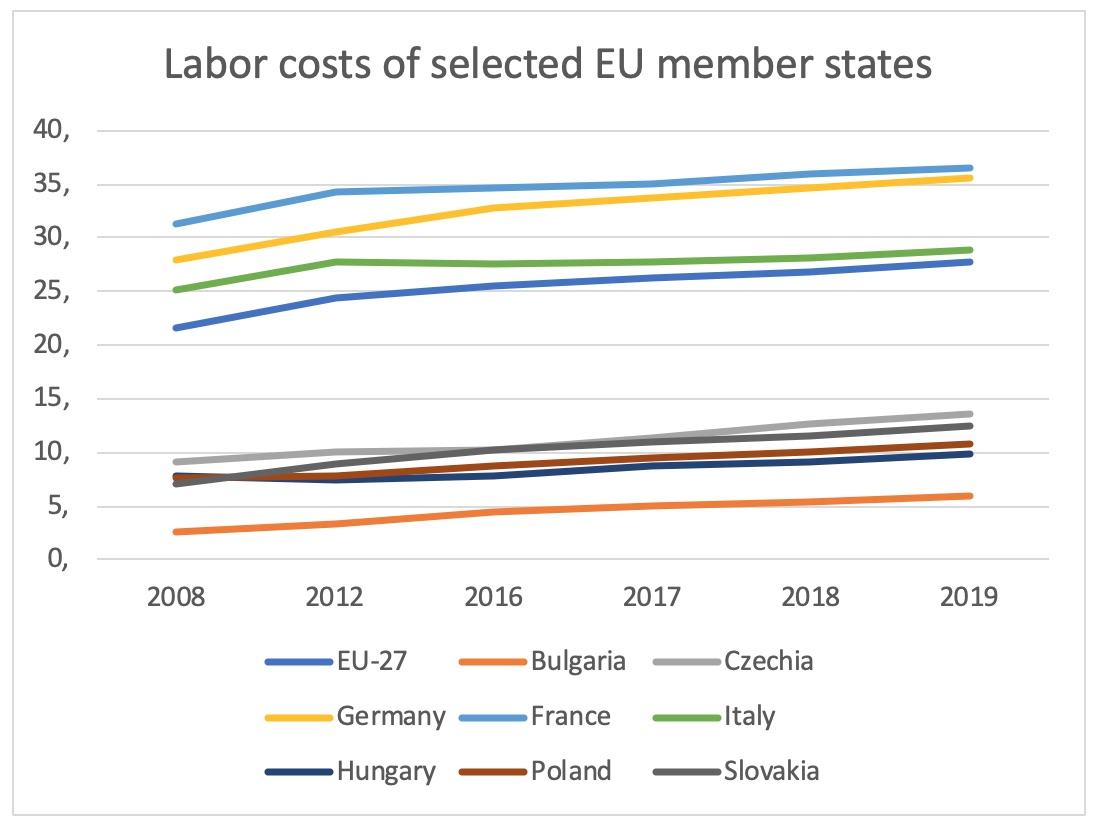

In the case of a move back to Europe, Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries appear to be preferred, due to their geographical proximity and considerably lower labor costs compared to those in Western European. For example, the labor costs in CEE countries remain around 1/3 of those in Germany (figure 1). Although they may still be higher than in China, the shortened delivery times and a higher quality of production can compensate for the already narrowing labor-cost gap between these countries and China, according to data collected by the Europe Reshoring Monitor Project[1].

Figure 1 - Data source: Eurostat

In May 2020, the Polish Institute of Economy published a report (in Polish) indicating that the CEE countries could gain up to 22 billion USD annually[2] following relocation of production from China. Poland is estimated to be the one to benefit the most in absolute terms with up to 8.3 billion USD of value added annually. Those CEE countries set to gain the most relatively from this trend are Slovakia (+ 2.84%), Czech Republic (+ 2.75%), and Hungary (+ 2.36%)[3].

2. Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia has always been the preferred choice when seeking alternative options outside of China. Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia seem to be by far the biggest winners in this trend. Analysts generally attribute this to three factors: geographical proximity with China, openness to foreign investment and low labor costs. Among the three, Vietnam stands out, thanks to its free trade agreement with the EU. This entered into force on August 1st of this year, immediately eliminating tariffs on 70% of goods.

The main disadvantages of Vietnam are its small domestic market and reliance on foreign supply of intermediate and raw products, particularly from China. During the early days of the outbreak of the pandemic, as China extended its New Year holiday, Vietnamese textile factories faced a severe supply shortage of material. However, these disadvantages are not restricted to Vietnam, but apply to other potential options such as Thailand.

Other more populated Asian states, such as India and Indonesia, could be seen as more attractive owing to the size of their domestic markets. However, their lower degree of integration into the global value chain and their environment less conducive to FDI are the major barriers for investors wishing to relocate.

Which “plus One” to choose?

1. Back to Europe

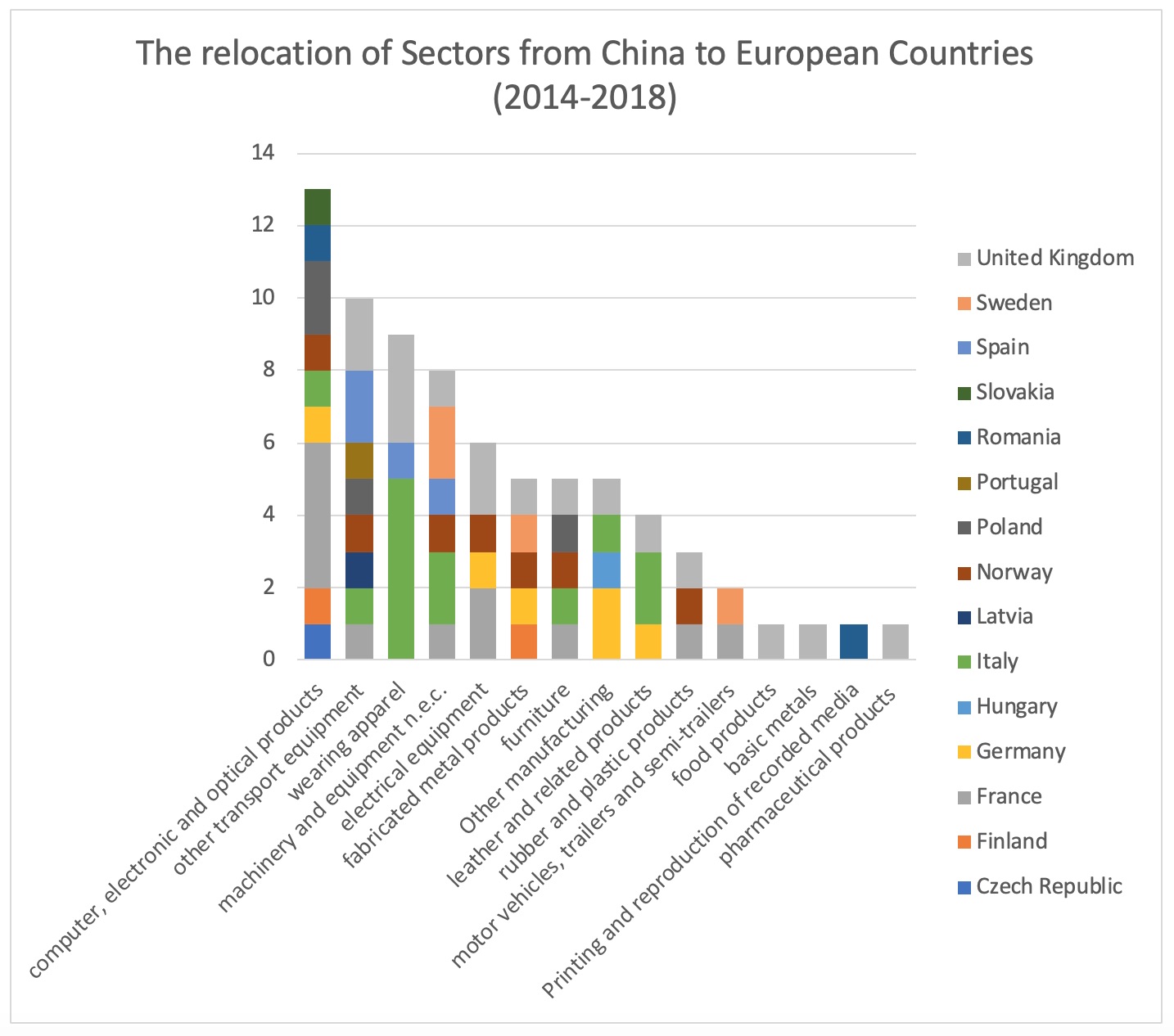

The choice of moving back to Europe or diversifying in Southeast Asia is industry specific. According to the UNCTAD 2020 world investment report, reshoring to Europe would be more adapted to high-tech firms with a deeply integrated global supply chain, and requirements for automation in manufacturing. According to the Europe Reshoring Monitor project, between 2014 and 2018, 76 firms moved back to Europe from China and automation was a reason for around one quarter of them. A recent article published by VoxEU estimated that the pandemic is likely to cause à 35% drop in the global value chain and accelerate the adoption of robots in production by more than 70%. Moreover, this trend is helped by the fact that the cost of robots has considerably dropped following the global crisis of 2008-2009.

For some strategic sectors, government initiatives are the main driving force behind reshoring. This is particularly the case in Europe for electric car battery manufacture and the pharmaceutical industry. The pandemic has served as a wake-up call for the EU, initiating the push to bring pharmaceutical production geographically closer to home. A similar move can be seen in America’s semiconductor manufacturing industry.

Figure 2 - Source : Europe Reshoring Monitor Project

- Diversifying in Asia

Countries in Asia with low labor costs remain a preferred option for low-tech sector industries, such as textile manufacturing. A move to automated manufacturing processes in this sector is not supported by a cost-benefit analysis. This is, however, not the only consideration to be taken into account. The “made-in effect” means European goods are more appealing to consumers, and this appears to be a common reason behind the decision of several apparel and leather goods manufacturers, notably from Italy, to reshore in the past few years (Figure 2).

However, the established supply chain cluster in East Asia can create a "lock-in" effect forcing factories to choose Asia rather than a move back to Europe. One typical case is Adidas' decision to move production back to Vietnam and China in 2020 after having established two automated factories (“Speedfactories”) in Germany and the US in 2016. The decision was driven by the importance of being close to "suppliers and know-how".

Increasing Demand for Intra-regional Shipping

Whether it be a move back to Europe or diversification within Asia, intra-regional shipping could experience an increase in demand. Companies seeking to diversify their supply chain with suppliers from Southeast Asian countries means intensified intra-regional shipping connections with China. Some of the popular relocating sites are also the leading importers of Chinese intermediate goods.

In the first half-year of 2020, the container shipping throughput of Beibu Gulf ports, the Chinese gateway to Southeast Asia, increased by 33.7%, against the global decrease. According to a market update published by DHL, the outlook for intra-Asia shipping sees an increase of 5.4%, which equates to 33.3 million TEUs from 2020 to 2024, the highest increase in volume of all major trade lanes.

[1] In the Europe Reshoring Monitor Project, nearshoring to another EU country is regarded as reshoring.

[2] The estimation is based on four scenarios, the highest profit comes from that of a mix of national patriotism and the growing importance of Central European countries. The least gain comes from a scenario where firms seek alternative sites in Southeast Asia.

[3] This percentage is also under the scenario of a mix of national patriotism and the growing importance of Central European countries.